|

Photo by Debra Lopez

|

|

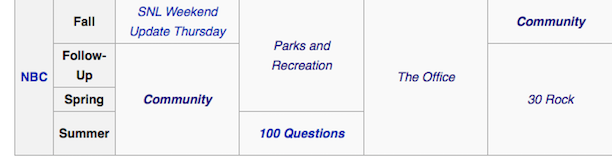

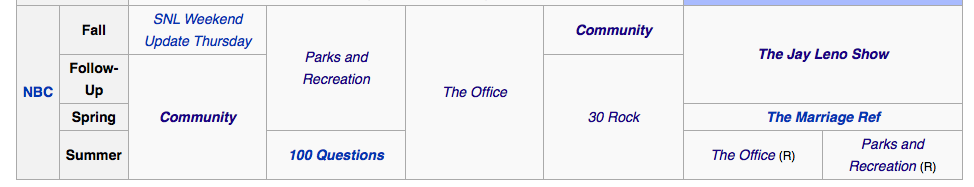

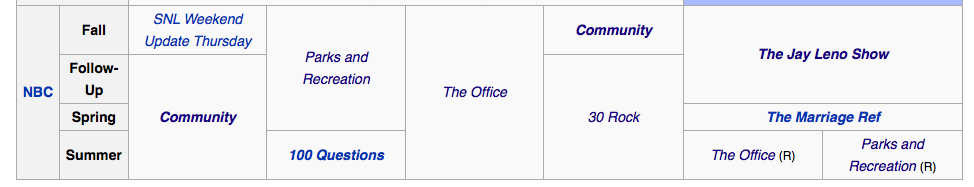

The Bernie Mac Show was 1 of the most brillantly conceived and executed sitcoms in decades. It brought me back to television. We've yet to hit that mark again. ~AYT By Darren Franich http://www.ew.com/article/2015/03/19/office-and-decade-great-nbc-comedy When The Office debuted ten years ago, it was not a very good sitcom. At that point, most sitcoms weren’t very good. This was the era of Arrested Development, yes, but also a slew of bargain-bin family comedies—goofy-husband/hot-wife multicams like According to Jim and My Wife and Kids, and Yes, Dear. The family multicam’s best-case-scenario, Everybody Loves Raymond, was moving towards its final act; heir apparent The King of Queens would soon make way for Two and a Half Men and the Chuck Lorre juggernaut. The early 2000s was marked by attempted star vehicles forgotten to time: Wanda Sykes’ Wanda at Large, Luis Guzman’s Luis, Whoopi’s Whoopi, Bette’s Bette. The Bernie Mac Show was a bit of both—half comedian star vehicle, half family comedy. In hindsight, Bernie Mac looks like the Mitochondrian Eve for half the comedies on TV now: Modern Family’s mockumentary-melodrama, Louie’s acerbic-yet-poignant take on contemporary parenting, black-ish’s postmodern identity politics. Bernie Mac deserves more praise, but it was also a victim of the network age: Creator Larry Wilmore got fired in the second season, apparently because Bernie Mac wasn’t normal enough. (He’s last-laughing now.) The Office debuted on Thursday, March 24, 2005, before quickly moving to Tuesdays for the rest of its first (short) (bad) season. There wasn’t much room for comedy on Thursdays at that moment. NBC circa 2005 wasn’t as bad as NBC circa every year afterwards; still, things were trending downwards. In May 2004, NBC lost Friends and then Frasier, two Thursdays in a row. The Friends loss was bad for ratings. The show was never unpopular; the series finale got over 50 million viewers. (“Over 50 million viewers” is a phrase that barely exists anymore.) But the Frasier loss may have hurt more on a purely psychological level. Frasier spun off from Cheers; losing it meant losing a healthy continuity, two decades of sitcom dominance, of Must-See TV as a signifier of critical and commercial success. NBC would never have both again. And over the next decade, the network would constantly try to sacrifice the former in vain pursuit of the latter. When The Office aired its first season, the NBC Thursday was a portrait of fading glory. There was failed spinoff Joey; there was decline-period Will & Grace; there was ER, in the final year of Noah Wyle, falling out of the top 10, and completing the tricky transition from buzzy ratings juggernaut to steady-but-unimpressive good-earner—kind of like Grey’s Anatomy three years ago, or The Walking Dead three years from now. NBC was so nakedly desperate for a new Friends that it greenlit Coupling, a remake of a British show that was itself a remake-in-everything-but-name of Friends. (By comparison, imagine AMC greenlighting a remake of Revolution and adding zombies.) The first episode of The Office wasn’t good; it was a pretty direct repeat of the British Office’s pilot, translated in the worst way from realcore Britcom into broadcast sitcom. But The Office’s initial badness is part of its mythology now—one of the great tales of TV course correction, right up there with adding Julia Louis-Dreyfus to Seinfeld and pretending season 2 never happened on Friday Night Lights. The show found its footing quickly after its first finale. Season 2’s opening episodes are pretty much sitcom transcendence: “The Dundies” and “Sexual Harassment,” “Office Olympics” and “The Fire,” episodes much loopier and more absurdist than the British mothership—all of it climaxing in “Halloween,” with a sequence that’s at once goofy (everyone’s in Halloween costumes) and bleak (somebody gets fired, and Michael goes home all alone). The names behind these episodes echo forward across the decade: Greg Daniels, Michael Schur, Paul Feig, Mindy Kaling, BJ Novak. They also echo backward: Ken Kwapis directed a couple of these episodes, plus The Office’s pilot and its eventual series finale. Kwapis helmed some of the great episodes of The Larry Sanders Show, the pilot for Bernie Mac, and a swath of episodes for Malcolm in the Middle, the show that pretty well cemented single-cam comedy as a going concern on network television. The Office never got huge ratings. It ranked 67th among network shows in its second season, ultimately batting cleanup on a two-hour comedy block that included Will & Grace, the forgotten Four Kings, and the declining My Name is Earl. But the numbers were steady—and they looked better and better while everything else on NBC did worse and worse. It was a centerpiece series in the reimagination of what, precisely, could define success in television: You always heard NBC brag about the high-priced demos the show drew in. More importantly for history, The Office was moving the chains on sitcom craftsmanship. Season 2 saw the show move decisively outside the realist perspective of the original British Office. This usually gets described in the lamest possible way—the show became more “hopeful” for American audiences, or “nicer.” As a pure achievement in the artistry of whatever TV is now, I’m not sure you can even compare Office UK, which ran for 14 episodes (including Christmas specials), to Office US, which ran for 201: It’s like comparing a novel to a comic strip. But as a pure achievement in rewriting the rules of the American sitcom, I don’t know how you compare anything to The Office’s early seasons, which supercharged the workplace sitcom in every direction. The Office reflects the tipping point when the riffy rhythms of improv comedy staged a full-scale invasion of Hollywood. The show undoubtedly benefited from a happy accident of history—who could’ve guessed that a genial, low-key comedy directed by the Undeclared guy would turn Steve Carell into a movie star?—but remarkably, the show didn’t become The Steve Carell Show. Instead, The Office benefited from a deep bench of talent: The show could depend on Phyllis and Meredith, on Oscar and Stanley, on the one devastating Creed non sequitur per week. It also benefited from the sudden vogue for serialization. The Office debuted at the tail end of Lost’s first season, and you can see how the success of that show emboldened the comedy. The series conjured up an excellent will-they-or-won’t-they between Jim and Pam, then gave the couple a cliffhanger kiss at the end of season 2. But the show opted out of the Ross-Rachel purgatory, pairing off its central lovers early in season 4 and making way for further explorations with the supporting cast. The Office gets a bit unsteady in its middle years. You can usually measure an episode’s quality against how much time they spend outside of the office. But not many shows could manage high-tension cringe comedy and exultant sincerity, featuring episodes both as bleak as the fourth season “Dinner Party” or as earnestly romantic as the sixth-season Pam-Jim wedding. 30 Rock debuted about 18 months after The Office. It was a very good sitcom pretty much right away, and never stopped being a very good sitcom. The Office’s origin story will always be wrapped up in course correction. 30 Rock’s origin story has less strife and more irony: It was the other show about Not Saturday Night Live, the cheap little sitcom NBC greenlit the same year as the expensive Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, which got a complete first-season order before the pilot was even filmed because it was so obviously going to be a hit. This was not the first time NBC made a hilarious blunder by paying big money to fading stars of the network’s yesteryear. (Studio 60 starred Matthew Perry, late of Friends.) It was also not the first time NBC lucked into a masterpiece. 30 Rock did course-correct, subtly. Early on, it was clearly a “behind-the-scenes” comedy. But by the middle of season 1, it was a latter-day Looney Tunes. 30 Rock also became, in a weird way, one of NBC’s best advertisements for itself: By making its own network into the show’s Big Bad, the series cauterized some of NBC’s self-inflicted wounds, making the declining calamities of the Zucker era look like genial tomfoolery. 30 Rock felt completely different from The Office. Where one brought an awkward reality to the sitcom, the other hyperbolized the form into complete unreality. Where The Office earned a lot of mileage from how it built empathy for its basically-good characters, 30 Rock earned a lot of laughs from pushing its cast into deeper spirals of venial larceny. This is why it didn’t really matter that 30 Rock had more useless characters—bless Scott Adsit for seven years of just kinda being there. You could argue that The Office was a more impressive comedy achievement because it tried to create human characters, or that 30 Rock was more the more impressive comedy achievement because it was actually funnier. Undoubtedly, 30 Rock won all the Emmys The Office didn’t win. (Kinda literally: The Office won the Best Comedy Emmy precisely once, the year before 30 Rock debuted.) Also undoubtedly, The Office always got higher ratings than 30 Rock. Most undoubtedly of all, there is not a better or more interesting lineup in the modern history of the American sitcom than the middle of the 2009-2010 TV season, when this happened: That’s season 6 of The Office--not a great year, but a solid one, with a wedding and a baby and all the other hallmarks of a good show that should probably end before it gets bad. That’s season 4 of 30 Rock, when the show started to embrace its later period as a cameo-happy joke factory. (“Would you like to yell at the moon with Buzz Aldrin?” says Buzz Aldrin.) That’s the second season of Parks & Recreation, another one of the great TV course corrections—They Made It More Hopeful!—but also one of the flat-out best seasons of any television show, a mix of world-building serialization and character-defining moments. And that’s the first season of Community, a show that harkened back to much older sitcom traditions—creator Dan Harmon is a devotee of Cheers, and on the page Community looks like a lot of other misfit-family TV shows—while aggressively exploding all those traditions. I dunno. How do you beat that? There are great sitcoms on television now: Veep and It’s Always Sunny, Bob’s Burgers and black-ish. There are Fox comedies that feel like NBC comedies: New Girl, The Mindy Project, Brooklyn Nine-Nine. There are shows that skirt the line between “sitcom” and something weirder: Louie, Broad City, Man Seeking Woman. There are sitcoms too pretentious to realize they’re sitcoms: Girls, Togetherness. You could argue that the best comedy on television right now is in sketch—but I think you can still draw a line from the Silver Age of NBC Comedy to Key & Peele or Inside Amy Schumer. Crucially, none of these shows have ever aired all together at the same time, one-two-three-four in a row. The Office, 30 Rock, Parks & Recreation, and Community did. Kind of. For a little while, intermittently, often broken up by NBC’s vain attempts to make other, worse shows happen. This was the real end-of-empire era for NBC. Let’s take an expanded look at that 2009-10 schedule, shall we? NBC tried to turn a primetime show into a late-night show. Coasting on past glories, paying big money for aging legacy talent on the assumption that ratings would soar: Does this sound familiar? When Jay Leno failed, the network hired Jerry Seinfeld to kinda-host The Marriage Ref. 2011 brought The Paul Reiser Show; 2012 brought Go On, with Matthew Perry once again. (In 2011, NBC moved 30 Rock back to 10 PM to make room for Perfect Couples, which is like Coupling for people who thought Coupling wasn’t Coupling enough.) I’m being cruel to be kind, but when 30 Rock and The Office aired their final seasons, this is what the NBC schedule looked like: When The Office went off the air two years ago, it was not a very good sitcom. A couple seasons without Steve Carell had taken their toll. The show can take some credit for bringing James Spader back to television and giving him a year to workshop his delightful-sociopath routine—which he’d soon leverage to grand effect in The Blacklist, an out-the-gate hit that NBC is smothering with love, just like all the network’s out-the-gate hits post-Friends. None of the Silver Age NBC sitcoms were big hits. Maybe that’s why they got away with so much. NBC was kind to the The Office because the demos were there, kind to 30 Rock because of the accolades and the Lorne Michaels factor. But Parks & Recreation and Community never had any ratings, nor Emmy love to speak of. They had cult followings and critical consensus, but you always felt like NBC would’ve cut them if any of its other shows had been successful. They weren’t. Last season, NBC aired Sean Saves the World and The Michael J. Fox Show—a throwback featuring the breakout star of Will & Grace, the glossy return of Fox to his Family Ties network. It ordered a full season of Michael J. Fox, sure the show was going to be a hit. (For good measure, the network also ordered Welcome to the Family, a dumb-dads-’n-smart-wives family sitcom starring Mike O’Malley. The ghost of Yes, Dear walks!) None of those shows lasted another year. Community’s comeback fifth season ended with a gag about fake NBC shows: Thought Jacker, Intensive Karen, Mr. Egypt, Celebrity Beat-Off, Captain Cook, all debuting sometime, whenever. “Depends on what fails!” In that moment, Community’s run on NBC ended. Maybe it’s a coincidence; probably not. Right now, NBC’s Thursday starts with The Slap. (What could 30 Rock have done with The Slap? Would it even have needed to do anything?)

The final gasp of NBC Comedy Thursday’s Silver Age took place last month, on a Tuesday, with the series finale of Parks & Recreation. Parks & Rec wasn’t The Office; it was less popular and better, carrying forward and expanding its predecessor’s legacy. But Parks has no clear successor. NBC’s big plan for its future is what worked in the past: more Dick Wolf, more Lorne Michaels, more Heroes, God help us. This spring, NBC was going to debut The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, starring Office alum Ellie Kemper, created by 30 Rock’s Tina Fey and Robert Carlock, with a pilot directed by Community veteran Tristram Shapeero. Instead, Kimmy Schmidt went to Netflix, leaving television behind. The comedy auteurs themselves couldn’t have scripted a more fitting end for an era.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed