|

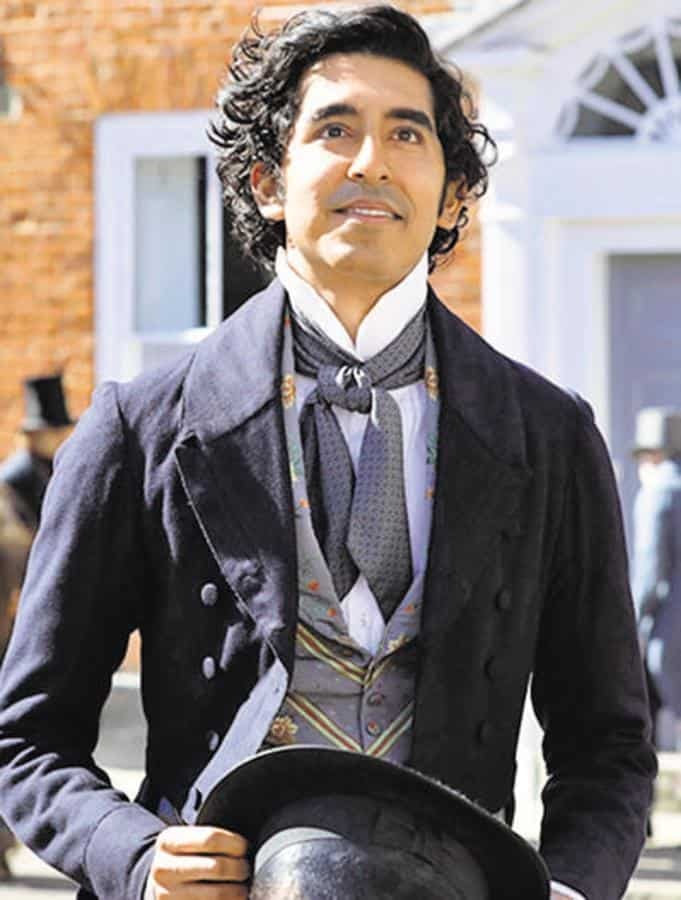

Photo by Debra Lopez

|

|

The short answer is because we finally have enough actors of color with visibility and box office success who can be cast according to their emotional type. Once you deal with the financial realities of getting a film made (namely a star with serious box office numbers), it allows the artistry of casting to come alive. The ability to look at a human being understand what their deepest emotional chords are and cast them accordingly. It's a powerful thing for actors/writers to know their emotional chords. It allows you to go after and create roles for yourself that might otherwise not exist. This is a turning point for artists because finally, the thing that truly makes their work unique, their emotional chords are what determine who gets the role.  Like most cheap paperbacks of David Copperfield, my battered old copy features a cover illustration of its eponymous hero as a boy: rosy-cheeked and blue-eyed under a nest of golden ringlets. (The artist gets it a bit wrong with the cruel smile, more horror movie kid than darling innocent, but hey ho.) On dustjackets and on screen, David Copperfield has been pale and posh ever since Charles Dickens published the novel he called his “favourite child” in 1850. (The BBC’s 1999 adaptation starred a pre-Harry Potter Daniel Radcliffe.) But, in a landmark instance of “colour-blind” casting, Dev Patel, a Londoner of Indian heritage, is to play Copperfield in a new film by Veep’s Armando Iannucci. On the phone from the Ealing Studios set of The Personal History of David Copperfield (the film is out next year) producer Kevin Loader tells me that Patel was simply the right person for the job. “In all our conversations, we never spoke about another actor to play our lead than Dev,” he explains. “We often have lists for parts, but we never had a list for David Copperfield.” You can see why Patel is perfect. Dickens’s story is the tale of an orphaned boy making his way in the world and finding himself as a man. That is precisely the kind of innocence and experience story in which the Slumdog Millionaire and Lion actor shines – with all that boyish eagerness and puppy dog warmth. Scarlett Johansson in Ghost in the Shell, casting that drew accusations of whitewashing. Photograph: APBut it is not just Patel. The cast of The Personal History of David Copperfield resembles the top deck of a bus in any big British city. Benedict Wong is Mr Wickfield. Rosalind Eleazar plays Copperfield’s true love, saintly Agnes. Dastardly Steerforth is portrayed by a white Welsh actor (Aneurin Barnard) with a Nigerian-born Brit, Nikki Amuka-Bird, as his mother, Mrs Steerforth. “Armando always knew he wanted Dev,” says Loader. “Once you realise that, then you’re making a statement about the fact that you’re going to cast actors who are capable of embodying the character as perfectly as possible, regardless of their ethnicity. I was standing on the side of the set the other day, watching a scene between three of the younger characters. I suddenly realised I was watching three young black British actors in a Dickens adaptation, none of which were written as black characters. And it didn’t seem odd. It’s just another scene in the film.” AdvertisementLoader makes the point that London in the 1840s was more diverse than costume dramas tend to depict. “London was the centre of a huge global empire and was full of everybody. Just as it’s a global city now. Traditionally, Dickens adaptations haven’t reflected that.” David Copperfield might be a blip, or perhaps we will look back and say it redefined the casting status quo in British film. Theatre audiences have been happily watching actors who don’t match the ethnicity of their characters for years, although not without controversy. Last week, Beverley Knight defended her right to play Emmeline Pankhurst in a new suffragette musical in London’s West End. Two years ago, JK Rowling called people who criticised the casting of Noma Dumezweni as Hermione in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child “racists” – pointing out that she never specified the ethnicity of Hogwarts’ clever clogs. On stage, “colour blind” has often been used to describe casting that ignores ethnicity. But it is a term that many actors of colour reject, since it is impossible for audiences to suddenly become blind to race, as the Shakespearean actor Debra Ann Byrd explained in a Guardian interview last year. Loader has been using the phrase “colour inclusive”. I ask him why film has lagged behind theatre in diverse casting. “I’m sure it’s something to do with that feeling behind it somewhere that photography tells the truth. Film seems a kind of realist medium to lots of people, which is odd, because most films are fantasies these days.” Beverley Knight (second left) as Emmeline Pankhurst in Sylvia at the Old Vic. Photograph: PRWhen you stop to think about it, the logic of literal casting quickly comes unstuck. In the upcoming drama Mary Queen of Scots, the Irish actor Saoirse Ronan is playing Mary; no one would argue that her Irishness is damaging to authenticity. (To be truly accurate, the role would require the casting of a Scottish actor mostly raised in France). In fact, Mary Queen of Scots is another film with casting that crosses ethnicity lines, with British-Chinese actor Gemma Chan playing Mary’s jailer, the powerful aristocrat Bess of Hardwick. Femi Oguns is an agent who opened the Identity School of Acting in 2003, frustrated at the lack of opportunities for black and ethnic-minority actors; its alumni include John Boyega and Chewing Gum’s Michaela Coel. Oguns then set up a talent agency, the Identity Agency Group. He tells me he is seeing “more scripts than ever” being produced with non-traditional casting. “For this to happen in narratives where the race of a character isn’t specific to the plot or pivotal in their portrayal is a wonderful step forward. I believe audiences are far more accepting of this than we perhaps give them credit for. Suspension of disbelief kicks in fairly soon after the opening credits. Some of it still errs on the side of being gimmicky, but we have seen a real appetite for change.” Nevertheless, he adds, scripts featuring black and ethnic-minority characters are often depressingly stereotypical. “We end up with the same old stories over and over. Gang violence in inner-city London, religious extremism, FGM, drug dealing, terrorism. There’s no light and shade in what we are afforded, there’s no space for it, therefore cliches are king. We are starting to see change at the top, we are seeing complexity come through. It’s slow going, but I am hopeful we are moving in the right direction.” Colette, a new biopic of the French writer starring Keira Knightley and directed by Wash Westmoreland, features two actors of colour playing historical figures who were white in real life: Asian-Brit Ray Panthaki and the black actor Johnny K Palmer. Additionally, a trans man, Jake Graf, has been cast in a cisgender role, while the trans actor Rebecca Root plays a cisgender woman. There was also a trans consultant on the film. Colette’s producer, Elizabeth Karlsen, tells me that the casting felt right in the context of the rule-breaking, convention-busting times in which Colette lived. “We just wanted to be outside the box like Colette was as a person. And just trying to change things.” What term has she be using to describe the film’s casting? “What you really want the word to be is ‘casting’,” she says dryly. “But we’re still in a world where you have to define it as something different. Hopefully one day that won’t be the space we’re in.” At the same time, however, Hollywood whitewashing has become toxic. Last year, Ed Skrein pulled out of playing an Asian-American character in the Hellboy reboot. Scarlett Johansson was criticised for playing a character in the Hollywood version of Japanese anime Ghost in the Shell. Double standards? Not when you consider how few opportunities there are for actors of colour without white actors coming along and hoovering up the decent parts. Femi Oguns (left), the founder and CEO of the Identity drama school, with three former pupils (left to right) Adelayo Adedayo, Tobi Bakare and Malachi Kirby. Photograph: David Levene/The GuardianNot everyone is 100% behind colour-blind casting. Critics argue that while it addresses the need for diversity, it fails to address the shortage of films that represent the lives, experiences and histories of people of colour. When the Selma actor David Oyelowo gave a keynote speech at the London Film festival two years ago, he got the biggest cheer for saying that black British history didn’t begin with Windrush. He explained the catch-22 situation he found himself in as a producer, trying to get a film financed about Bill Richmond, the superstar 18th-century bareknuckle boxer who was born a slave and later lived in London. A rejection letter from a film exec told him that when it came to historiwww.theguardian.com/film/2018/aug/17/why-dev-patel-in-dickens-could-change-film-for-evercal drama they would only consider “a piece of history ripe for a revisit”. As Oyelowo put it: “If my British history has never been visited, where does that leave me?” Loader tells me that David Copperfield isn’t about colour-conscious casting; he just wants people to accept the actors as playing their characters. “It’s not a book about racial politics and we’re not trying to make a version of it that comments on racial politics. We’re just trying to make a version that comments on the diversity of humanity I suppose.” I ask him if the casting isn’t just a little bit calculated? British film feeds us an endless diet of bonnets and breeches; now here comes a headline-grabbing Dickens, making the genre fresh and accessible for a contemporary audience. “No,” he insists. “It wasn’t done cynically in that way. I think we felt this was how you’d get the best cast more than anything else. And suddenly you can have Benedict Wong coming in to play Mr Wickfield, and he’s hilarious. He wouldn’t have been cast in the BBC version of David Copperfield. TheGuardian

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed